“Operation Hardgate” was in full swing on August 1, 1943.

Begun on the 29th of July, this was a pincer maneuver to capture Adrano. On one pincer was the 1st Canadian Division at Regalbuto and the other was the 78th Division, supplemented with the 3rd Canadian Brigade.

The Germans, particularly the Panzer-Division Hermann Göring, were told to hold the line, but had been bombed continually by the RCAF flying out of Tunisia. Once again, the Panzer-Division Hermann Göring were matched against the Canadians in Regalbuto.

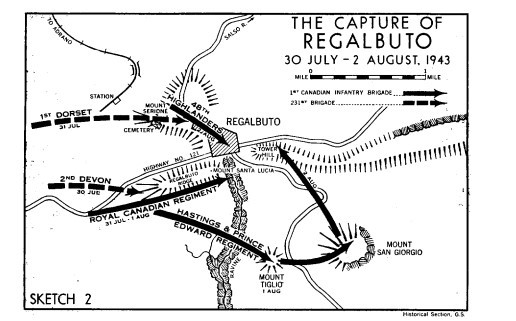

The map below comes from Official History of the Canadian Army in the Second World War, Volume II, THE CANADIANS IN ITALY, 1943-1945 pg. 148. https://www.canada.ca/en/department-national-defence/services/military-history/history-heritage/official-military-history-lineages/official-histories/book-1956-army-ww2-2.html

This is a great illustration of just how mountainous the conditions were in Sicily.

Due to this terrain, mules were used to transport almost everything, including the wireless No.22 set. This newest method of transportation often carried a No. 22 set on one side with two six-volt batteries on the other. The operator could walk alongside with microphone and earphones plugged to his set. It was not uncommon for the mules to also be burdened with rifles and other articles of kit. Mules were sometimes obstinate, died in combat and under fire would run away.

“When troops stopped for a break you dared not let the mules stop. They might decide not to go on again. If they saw a patch of delectable green grass they invariably forgot about the war. Once things became hot at BHQ and, perhaps because of the tracers flying around, my mule decided to retreat. This he did, unannounced, leaving me holding the microphone and earphones.” History of the Royal Canadian Corps of Signals, pg. 130.

Despatch Riders were sometimes the only way of reliable communications with the hilly terrain. For this reason, every time Major-General Simonds wanted to see the front line, first by jeep and then by tank, he was accompanied by a Despatch Rider as back up. The General’s jeeps would have one or two wireless sets and carry an operator for the tank set so he could be in constant contact with Headquarters and formations. Signallers found that the need for providing wireless communication for their commanders meant their primary assignments were as part of the “commander’s rover”. Mobile wireless was a must on the fluid battlefield.

Regalbuto was captured on August 2, 1943.

“When the Canadians entered Regalbuto on the heels of the occupying troops of the Malta Brigade, they came upon a scene of destruction far more extensive than any they had previously encountered in Sicily. The town had received a full share of shelling and aerial bombardment, and hardly a building remained intact. Rubble completely blocked the main thoroughfare, and a route was only opened when engineers with bulldozers forced a one-way passage along a narrow side-street. For once there was no welcome by cheering crowds, with the usual shouted requests for cigarettes, chocolate or biscuits. The place was all but deserted; most of the inhabitants had fled to the surrounding hills or the railway tunnels. They were only now beginning to straggle back, dirty, ragged and apparently half-fed, to search pitifully for miserable gleanings among the debris of their shattered homes.” Official History of the Canadian Army in the Second World War, Volume II, THE CANADIANS IN ITALY, 1943-1945 pg. 152

Catenanuova was captured on July 30th by the 3rd Canadian Brigade and the push to Centuripe began with the 78th Division in command. Centuripe fell on August 4, 1943.

Now the final push to Adrano began.

“The 1st Canadian Division was told to take Adrano. Major-General Guy Simonds tasked 2nd Canadian Infantry Brigade’s commander, Brigadier Chris Vokes, with the operation. In turn Vokes created a battle group based on the Three Rivers Regiment and the Seaforth Highlanders of Canada, along with reconnaissance, engineer and artillery units. The commanding officers of the two major units met and concocted a plan that would see the infantry mounted on the back decks of the Three Rivers Regiment’s Sherman tanks. Preceded by a reconnaissance squadron from the Princess Louise Dragoon Guards, the force set out at first light (0600 hours) on 4 August. The first holdup was the railway bridge crossing the Salso River. The engineers had to be called forward to assist. Once across the obstacle the force gathered momentum. Closing in on the village of Carcaci, to the west of Adrano, the infantry dismounted. Fortunately, the enemy had no anti-tank guns. The Canadian tanks used their high explosive main armament rounds and their tracer machine gun ammunition to set fire to the dry grass and shrubs in the area. This had the effect of driving the German defenders from their cover. The village itself was pounded by the artillery. By mid-afternoon the objective had been taken with only light casualties to the Canadian force. With the Canadians now situated on the high ground overlooking Adrano, the Germans abandoned the town and retired to the north.” Credit: https://www.canada.ca/en/department-national-defence/services/military-history/history-heritage/battle-honours-honorary-distinctions/adrano.html

On 7 August the 1st Canadian Division camped at the foot of Mount Etna and went into reserve. Ten days after the 1st Canadian Division went into reserve, 17 August, marked the final victory in Sicily and the end of a short but trying campaign in which communications had played a vital part. Canadian soldiers had fought continually from July 10-August 7, 1943 and had proved their combat effectiveness and the ability of mobile wireless communications.

By September, 1943 the Canadians would be landing on the shores of Italy.

Karen Young, Museum Manager