With Operation “Husky” complete and the invasion of Sicily a success it is easy to assume that Canadian troops would be moving immediately into Mainland Italy. This in fact was not the case.

The Casablanca Conference in January 1943 did not deal with the question of what might happen in the Mediterranean theatre after “Husky”. American leaders thought that they should focus on the invasion of Normandy. The British believed that the removal of the Italians from combat would allow them to successfully focus on the invasion of Normandy in 1944. From the British point of view, it was unthinkable that their armies would remain inactive when Russia was so heavily engaged on the Eastern Front. The Americans did not believe that any offensive in the Mediterranean in 1943 could be on a large enough scale to draw off enough German forces from the Russian front. They feared that such a campaign would weaken the Allied resources and not change the deployment of German troops to the Western Front. The Americans wanted to have only limited operations in the Mediterranean area after the completion of “Husky”.

By mid July 1943, with the swift progress of Operation “Husky”, the Allies decided to go ahead with the invasion of the Italian mainland. The Allies hoped that by acting quickly, they would minimize German efforts to reinforce southern Italy. The fall of Mussolini in late July also supported the decision to invade the mainland. The Canadian government approved the invasion of Italy on August 16, 1943. General Simonds began planning the Canadian assault and by August 24, the invasion plans of the Italian mainland were ready.

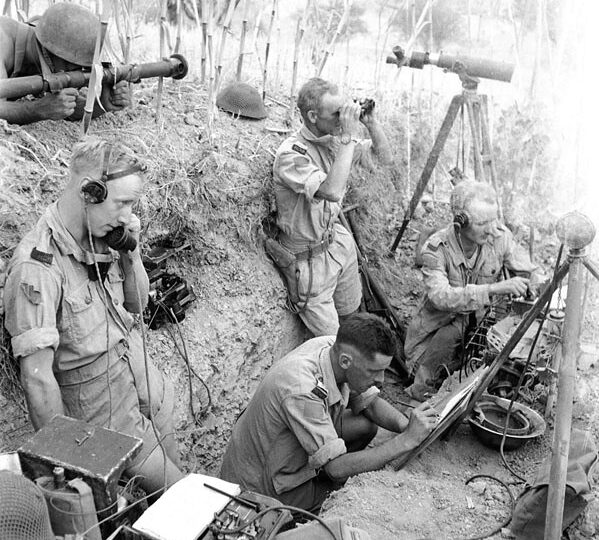

Operation “Baytown” commenced on September 3rd, 1943. The landing was unopposed by the Italian troops. A wireless aerial, connected to a doorway of the Governor’s Palace, directed the landing of the battalions in Reggio. There were so many wireless sets in use that Signals formed a Wireless Security Section to monitor Canadian wireless transmissions to be certain that sets were operating on their allotted frequencies.

On September 8th, Italy surrendered to the Allies. The Germans, prepared for the Italian betrayal, killed, captured and disarmed the

Italian Army over the space of two weeks. From then on, the Canadians were fighting only the Germans in Italy.

Canadian troops were able to move forward rapidly. By September 9th despatch Riders were traveling hundreds of miles to deliver messages. Wireless telegraphy, used extensively through the mountain ranges, was sometimes as far ahead as 220 miles of the main division. The Germans slowed the Allied advance by blowing up bridges, mining roads and creating machine gun nests at defensive positions.

By the end of September 1943, the American 5th Army had captured Naples and the Canadians and British were in the Foggia plains. The southern portion of Italy had been secured.

Written by: Karen Young, Museum Manager