Congratulations to the Royal Canadian Air Force for 100 years of service on April 1, 2024!

The RCAF was first conceived of in 1914 as the Canadian Aviation Corps (CAC) at the beginning of the First World War and was attached to the Canadian Expeditionary Force. The CAC had three personnel and one aircraft which was delivered but never used. By May 1915, the unit had ceased to exist.

Between 1914 and 1918, 22,000 Canadians served in the Royal Flying Corps (RFC) or Royal Naval Air Service (RNAS) with 25 per cent of the RFC officers being Canadians. During this time there were huge strides in air to ground communication that made the use of airplanes viable on the battlefield for reconnaissance and ground support.

Prior to the First World War wireless telegraphy (sending telegraph signals by radio) was used to communicate from the air to the ground. Its main drawback was its size. The battery pack and transmitter weighed up to 45 kilograms and took up an entire seat on a plane, sometimes overflowing into the pilot’s area. Due to the size of the equipment, there was no room for a dedicated radio operator. The pilot would have to do everything while flying over the objective: observe the enemy, read the maps, and tap out coordinates in Morse code, all while flying the plane under enemy fire. British pilots could communicate with each other using this method but it was very cumbersome.

The Sterling spark gap wireless transmitter, was the first purpose-built airborne wireless set used by the Royal Flying Corps (RFC) in the First World War. It was first produced in late 1914 and brought into use in 1915. The transmitter and Morse key were totally enclosed to avoid a spark igniting the petrol vapour in the aircraft cockpit. Communication was in one direction only so the sender, usually the observer in a two-person biplane, had no way of knowing if the message had been received or not. Later spark gap transmitters had both a transmitter and receiver.

The most significant development during the First World War was to the wireless sets themselves. They became more precise, due to the addition of more advanced radio vacuum tubes. These vacuum tubes also allowed for the development of radio telephony (voice communications). Because of the addition of a transmitter and receiver two-way communication became possible. By the end of the First World War, some British fighter aircraft on the frontline were equipped with two-way voice communications via wireless using flying helmets with headphones and throat microphones capable of communication over distances of over 10 miles.

In late 1918, Canada made a second attempt to create a military air force with the creation of the Canadian Air Force that did not thrive due to the end of the war. It was replaced in 1920 with an organization that had a more civilian focus. While it still provided refresher training to

veteran pilots, the Canadian Air Force (CAF) members also worked with the Air Board’s Civil Operations Branch on operations that included forestry, surveying and anti-smuggling patrols. In 1923, the CAF became responsible for all flying operations in Canada, including civil aviation. In 1924, the Canadian Air Force, was granted the royal title, becoming the Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF). Most of its work was civil in nature; however, in the late 1920s the RCAF evolved into more of a military organization.

Until 1934 the RCAF depended on the Royal Canadian Corps of Signals (RCCS) for the operation and maintenance of its communication systems. Several RCAF officers had been attached to RCCS for a course of instruction, but the primary responsibility for equipment and manning rested with the army. Due to budget cuts, RCCS informed the RCAF that they would no longer take responsibility for their communications.

In June 1934 four wireless operators transferred to the Royal Canadian Air Force to form the nucleus for the new RCAF Signals Branch. On 1 July 1935, the Royal Canadian Air Force Signals Branch was authorized and began taking over air force communications responsibilities from the RCCS.

During the Second World War, the RCAF Signals Branch was vital to the success of the war effort. Radar technology was in its infancy, very secret and very important to rapid communications. The importance of telecommunications came to the fore. This is evidenced by the size of the Telecommunications Branch in 1949. The RCAF Telecommunications Branch establishment was set at 165 officers and 1700 other ranks out of total RCAF establishment of 14,500. By 1962 the Telecom branch had expanded to 6000 personnel.

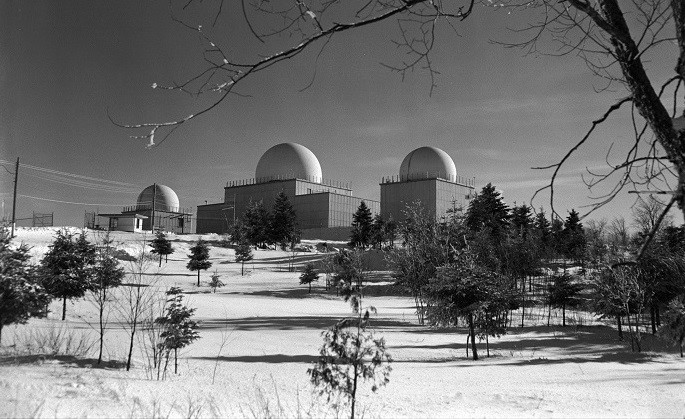

In 1951, the Pinetree Radar Line construction commenced as a joint Canada – USA project. Radar early warning stations were placed to counter the Soviet air threat against North America. Initial radar stations were fully manual air defence systems with both aircraft control and early warning functions. The stations were organized into geographical sectors. (As part of this expansion women were again enrolled in the RCAF [the wartime Women’s Division was disbanded in 1946] and by 1954 airwomen were eligible for overseas postings.) The Pine Tree Line was replaced by the Distant Early Warning Line (the DEW Line) by 1957. In 1988, the North Warning System (NWS) began operations, replacing the DEW Line and the remaining Pinetree Line stations. This is part of the joint US-Canada North American Air Defence (NORAD) System that continues operations to this day.

To all of the Communication and Electronics Branch Air Force Members, past and present, congratulations on your centennial!

Karen Young, Military Communications and Electronics Museum Volunteer